We talk to Eva Langret, curator of The View From Here at Tiwani Contemporary, about seven artists from across Africa, each capable of using photography to reclaim their own history.

“Photography in Africa is controversial,” says Eva Langret, curator of The View From Here, an exhibition showcasing photography from Africa and its diaspora at Tiwani Contemporary, displayed until the 27 June.

The camera, the exhibition posits, has been misused. Photographs have been misrepresented. It has objectified the African experience, and its relationships to past colonies. But, in recent years, the camera has also become a tool of empowerment.

The seven African artists exhibiting are aware of this contradiction. They have given up on using photography as a documentation tool and instead adopted personal and subjective approaches that speak, perhaps more accurately, of wider issues.

They seek to make sense of their personal narratives through collective history, between memories, the present and the self, in relation to our sense of place and belonging, of how photography can relate to, and comment on, other popular media and practices.

The work of Mimi Cherono Ng’ok greets us with shots of a strangely unanimated Dakar, the capital of Senegal. Before arriving in Senegal, she started to become familiar with the city through native television and films. Then, when she set foot in the city for the first time during the Dakar biennale, she made sense of this foreign place by shooting it. Yet she remains distant from her subject, as an aerial shot of a hotel swimming pool testifies. As such, it’s an alienating look at the more mundane elements of an African megacity.

© Namsa Leuba

Namsa Leuba gets closer to her subjects. With a background in fashion photography, she has worked for the likes of Vice magazine and i-D. For this series, entitled Acrobate, she worked in a more spontaneous way, employing the two acrobats who grip us with their presence and powerful gaze. But, as with fashion photography, there is a strong mise-en-scène of the body, accentuated by the artists’ pose.

These images stem from a book she created for her graduation project. “The book is mostly concerned with religious and cultural ceremonies in Guinea,” explains Langret. “She appropriated and translated that in a way that made sense to her.”

These four photographs were shot on the spot in Guinea (her mother’s homeland), in a makeshift studio with a backdrop made of sturdy striped fabric and using only natural light.

The work of Andrew Esiebo, the only artist in the exhibition from a documentary background, is not as playful. A man with shades on is guarding an entrance protected by a thin lace curtain. He looks straight at us and beyond the camera with a deep sense of pride.

Esiebo is interested in highlighting the complexity and nuance not evident in news reports. This particular photograph is issued from a series made while working with the gay community in Lagos, right at the time when anti-gay laws were passed in Nigeria. “It’s brave to do that kind of work in Nigeria,” Langret says.

© Abraham Oghobase

On the other side of the gallery, Abraham Oghobase presents five self-portraits. He is trapped, eyes closed, behind the glitches of a TV screen. The caption reads school girls or ebola virus in Lagos – the titles of current Nollywood productions. Oghobase is looking at our mediated understanding of reality, in fictionalised accounts of what is going on in Nigeria, discussed and dissected by the film industry.

“Nollywood is very reactive like that,” Langret says. “If something happens, it doesn’t take long for a movie to refer to it.”

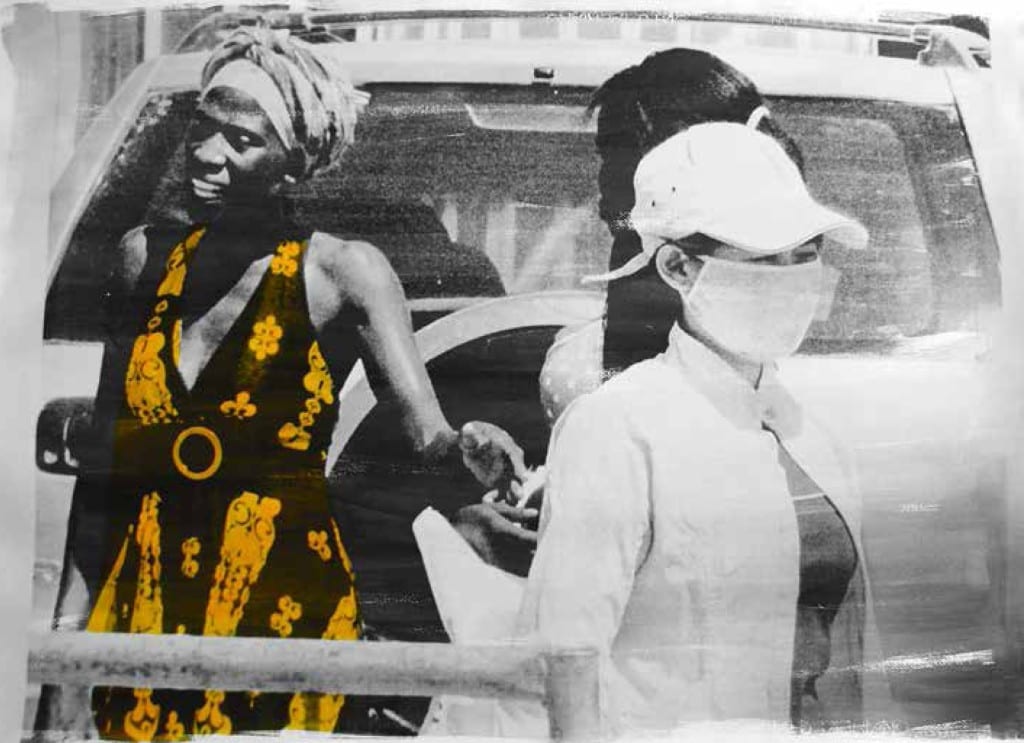

Delio Jasse moved to Lisbon from Angola when he was 18 and discovered photography via printmaking. He is concerned with the craft and the chemistry involved in producing images, working on a regular basis with cyanotype processes.

The four images exhibited here were born from liquid emulsions applied to fine art paper. As the photograph only appears where the emulsion exists: “He turned a reproducible object into something unique,” says Langret.

Using yellow watercolours, Jasse is capable of directing viewers’ eyes into details of the photo that we would not necessarily notice otherwise. The wider context for his work is documenting the new migration waves and social changes happening in Luanda.

South African artist Lebohang Kganye “has been unearthing the family archive”, says Langret. Kganye blew up photographs her mother kept to produce some lifesize cut-outs, allowing the chance to place herself in the scene. Here she re-enacts the narrative of her grandfather, who had to move often and changed his name many times because of the shift in land laws in the apartheid region.

The View From Here is exhibited at Tiwani Contemporary until 27 June 2015. More detailshere.

Stay up to date with stories such as this, delivered to your inbox every Friday.